The Three Kinds of Code You Write in the Newsroom

This is a lightning talk I gave at NICAR 2020. Since then, this framework has become the primary way I explain what programmers (like myself) do in newsrooms. You can watch a video of the talk here or click through slides here.

A couple years ago, I had one of those opportunities you don’t get often: I got to build a team from scratch.

Not a big team, there would be three of us, and we’d have a role in basically everything that required code on a small news site – from data journalism, to experimenting with new story forms, to a major site redesign.

As we got into the hiring process, I started making a list of all the skills we might need, so I could compare candidates.

- html

- css

- javascript

- php

- sql

- python

- git

- node

- d3

- photoshop

- illustrator

- wordpress

- excel

- R

- foia

- statistics

- scraping

- bash

- video editing

- after effects

- dev ops

- mapping

- ...

This got overwhelming pretty quickly.

I didn’t realize it at the time, but this was part of a problem I’d been struggling with in different ways since I started writing code for journalism, back when George W Bush was still president.

It’s a problem of language.

There’s an overwhelming number of skills and tools we use in writing code around news.

Most of those, and most job descriptions, are lumped together into titles like “news applications” or “interactives” or data journalism.

Then a few months ago, a friend asked me to talk to one of her students who was a talented photographer and also starting a comp sci program. And he wanted to know what to do with that set of skills.

And after talking to him and thinking about the jobs I’ve had, I realized that ultimately, there are three kinds of code we write in newsrooms:

Reporting. Storytelling. Product.

And that’s pretty much it.

So what do I mean by reporting, storytelling and product?

Reporting code is, well, reporting. It’s how we gather information and ask questions of it. It’s scraping, data analysis, machine learning and natural language processing. When you’re using SQL, R, Pandas and Jupyter notebooks, you’re probably writing code I’d call reporting. If you’re writing code to figure out if you have a story, I’d say you’re doing reporting.

Storytelling is, of course, what we do with all that reporting. It’s our graphics, interactive or not, and maps and charts and generative text. It’s AR and VR and 3D modeling. We know what we’re trying to say, because we did the reporting, and now we’re speaking with code.

And what is product? You might be thinking: We have another department that does that. They build the CMS and handle ad code, and I’m in the newsroom.

And I’m here to say, more of us are doing product than we realize.

Product is everything we build that isn’t for just one story or project.

It’s everything we do between deadlines that makes our next project launch faster or run smoother or get a little closer to what our audience needs. (In fact, it’s everywhere we talk about user needs.)

It’s anything we need to maintain, and anything that accumulated technical debt. (You might say it is the technical debt.)

It’s our app templates and starter kits that we update after we launch a project. It’s our longform tool. It’s our open source code. It’s our analytics packages and documented best practices.

An example: Ahead of the Fire

Here’s an example. This series – Ahead of the Fire – looked a wildfire risk across the Western United States.

In the reporting phase, my colleagues used GIS tools to ask which communities are most at risk, and which particular risks does each community face.

The storytelling side focused on explaining those risks and the methodology behind the story.

And here’s product: We call this the In-Depth framework, and it’s the machinary that powers our best storytelling.

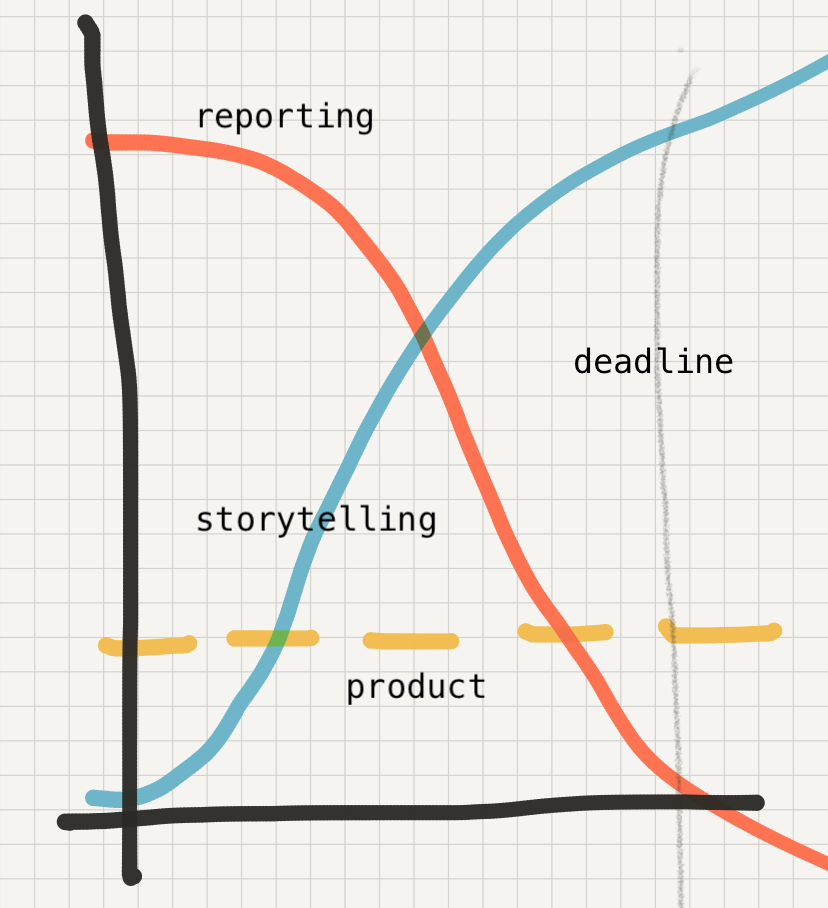

So why does it matter what we call these kinds of code? Because they move at different speeds. And every newsroom I’ve worked in has struggled at moving at different speeds.

Think of a project you worked on that went well. It probably started with a lot of reporting, which tapered off as the story solidified and you started to focus on storytelling. Meanwhile, product is (or should be) moving along in a steady cadence of sprints.

And this is where it’s important to know what kind of code we’re writing, and to be able to talk about it with other people in the newsroom, especially our editors. This is where it’s easy to screw things up.

This is where I’ve screwed things up.

Like trying to make something reusable too early: I wrote a Python client for the ProPublica Congress API because someone pitched a story related to Congress, and my response was to create a library. Cool. Never used it for a story.

Or falling in love with storytelling when it’s time to move into product: This story on Zika was great. We did a dozen like it, with a little variation, each one basically a bespoke Tarbell project.

After about the third one, we really should have started building tools into WordPress, but I was nervous about technical debt. This is where it helps to think in product terms.

Writing storytelling code that becomes technical debt: The original topper in this story was gorgeous. It was also built into our storytelling framework, which meant we were responsible for maintaining it. Forever. Oops. (We finally made it a static image.)

I’m sure you have your own examples.

Thinking about these three distinct kinds of code can help beyond individual projects.

If you’re looking at a job description, it’s a good way to get a read on what kind of job it is, and whether it matches up with your skills or career goals. You might use it to decide which NICAR sessions to go to.

It helps answer the question: “Should I learn [fill in the blank]?”

Now you can reframe it as:

- “What is X best suited for?”

- “How might X be used for reporting, for storytelling, for product?”

One last thing:

When I talk about three kinds of code, I want to be very clear that I don’t mean there are three kinds of coders.

As I said at the top, most of us are doing all three kinds of programming, and I think that’s a good thing, because it pushes us to be better and more well-rounded, both as programmers and as journalists.

Reporting and storytelling are still the core of our profession, and product is going to open up new ways of doing both.

We all have a lot to learn from each other.